Hiatal Hernia Repair

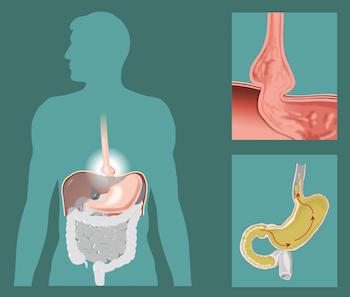

Unlike the hernias that most accustomed to hearing about, hiatal hernias are unique in that they cross between two body cavities: your abdomen and your chest. All of us have a small opening in the diaphragm known as the hiatus, which allows the esophagus to pass. A hiatal hernia involves the enlargement of the hiatus that then allows the upper portion of stomach to push through the diaphragm. Some people may be born with a hiatal hernia, and others acquire them with age.

Many patients suffering from obesity have a hiatal hernia and these are typically identified and repaired as part of a primary bariatric surgery procedure for obesity, or during a Nissen fundoplication or Linx Anti-Reflux Procedure for the treatment of GERD or gastroesophageal reflux disease.

There are four kinds of hiatal hernia – Type I, or sliding hiatal hernia, Type II, or paraesophaeal hernia, Type III, a combination of Types I and II, or Type IV, where other organs from your abdomen protrude into the chest along with the stomach.

Type I: Sliding Hiatal Hernias

Sliding hiatal hernias are more common and typically less severe of the four types. A sliding hiatal hernia occurs when the top part of the stomach including the gastroesophageal junction (where the esophagus and stomach meet) slides up through the hiatus and into the chest. The herniated stomach and gastroesophageal junction typically drop back in place soon after. Sliding hiatal hernias do not always need to be repaired if they are asymptomatic. Sometimes they are associated with GERD not amenable to medical treatment, at which point they may be repaired at the time of a Nissen fundoplication or Linx procedure.

Types II & Type III: Paraesophageal Hernias

Paraesophageal hernias are more severe and, if symptomatic, require more immediate care. A Type II paraesophageal hernia occurs when the gastroesophageal junction stays in place, but the top of the stomach herniates through the hiatus and lodges next to the esophagus. Typically, the stomach does not drop back down in place and the added pressure on the esophagus can cause problems swallowing and even ulceration, which in turn can cause anemia.

In a Type III paraesophageal hernia, a part of the stomach herniates into the chest like a type II, but the gastroesophageal junction “slides” with it, effectively making it a combination of a Type I and Type II hernia. These are typically bigger hernias compared to Type I and Type II’s, and can be more symptomatic. Both Type II and Type III paraesophageal hernias are usually repaired if they are discovered.

In rare situations with paraesophageal hernias, much of the stomach can push into the thorax and put pressure on the lungs and even the heart. The most dreaded complication of these hernias is if the stomach that is in the chest twists on itself, cutting off the blood supply to the stomach. This can cause the stomach to become ischemic or to die off, and requires emergency surgery to prevent.

Causes of Hiatal Hernias

We don’t fully understand how hiatal hernias form but many of the risk factors are similar to those of an abdominal hernia such as an inguinal hernia and include:

- Age-related decline in musculature

- Trauma to the diaphragm

- Congenital or hereditary factors

- Anything that can cause pressure at the diaphragm including obesity, pregnancy, persistent cough (especially in smokers), lifting weights and more

Symptoms of Hiatal Hernias

Typically, sliding hiatal hernias do not cause significant symptoms and most patients will not know that they have one. This is known as an asymptomatic hiatal hernia. Most patients are never screened for a hiatal hernia unless they have symptoms that cannot otherwise be explained or addressed. If symptoms do occur, they commonly manifest as a worsening in acid reflux.

Larger hiatal hernias and paraesophageal may be painful, and patients may have difficulty swallowing and even experience labored breathing, but are relatively uncommon representing only 5-10% of all hiatal hernias.

Most hernias are found incidentally, while looking for or treating other conditions. As a matter of course, we look for a hiatal hernia during any bariatric surgery procedure and correct it at the same time. We do this because bariatric surgery creates more pressure in the stomach, which can make the symptoms of hiatal hernias worse.

Hiatal Hernia Surgery

Depending on the size of the hiatal hernia, it may be repaired using sutures or a hernia mesh similar to that used with an abdominal hernia. However, because the hiatal hernia involves the esophagus passing through the hiatus even after repair, we avoid synthetic mesh as it has been known to erode into the esophagus over time. The preferred type of mesh is either absorbable (disappears after a few weeks or months leaving just your own healed tissue, or a biologic implant derived from animal protein. Virtually all hiatal hernias are, and should be, repaired using laparoscopy or robotic-assisted surgery – small incisions in the abdomen – versus open surgery. In the past, these surgeries required large abdominal or chest incisions, or a combination of both. They were painful and had a prolonged recover. With laparoscopic an robotic-assisted surgery, these procedures are usually outpatient procedures or involve a 1-2 day hospitalization. Recovery is anywhere from 2-6 weeks.

Symptomatic paraesophageal hernias are almost always repaired using a Nissen fundoplication where the upper portion of the stomach is wrapped around the lower esophagus and sutured in place. This is to prevent GERD from occurring even after the repair. Doing a partial fundoplication (Toupet or Dor type 270 degree fundoplications) or a LINX procedure, can also be performed at the time of hiatal hernia repair. Asymptomatic sliding hiatal hernias are usually observed, but can progress over time to larger, and symptomatic, hiatal hernias. Observation and surveillance are important for these, as the risk of having emergency surgery for a paraesophageal hernia is about 1% per year.

Good to Know Summary

- Asymptomatic hiatal hernias are not screened for and rarely treated

- Hiatal hernias will be repaired secondary to bariatric surgery to reduce the risk of reflux

- Paraesophageal hernias are riskier than sliding hernias

- Risk of emergency surgery due to a paraesophageal hernia is about 1% per year

- Main risk factors are obesity and age